trilingual

I met a friend at a coffee shop this week. When I walked up, the waiter greeted me in Russian, so I replied in that language, chose a table, and placed my order. When Ararat arrived, he greeted the waiter in Armenian and placed his order in that language. Ararat and I chatted in English, which is the home language of our friendship. Hearing this, the waiter switched to English to interact with us.

This is not at all unusual in Yerevan, and it amazes me every day.

I remember in graduate school learning about manuscripts from the British Isles after 1066 that were trilingual. The late 13th to early 14th century Harley 2253 manuscript, for example, includes Middle English lyric poetry and ink recipes, Anglo-Norman religious stories and poetry, and Latin saints' lives. The languages and genres are intermixed and each of the three scribes whose hands have been identified in the manuscript contributes in more than one language. I remember wondering what it was like to live in a trilingual society. How would you know when to use which language? How would you tell who spoke what?

In the England of the Harley scribes, language choice was partly situational. Latin for ecclesiastical things, and possibly some legal things. Anglo-Norman French for royalty and nobility. Middle English for the hoi polloi. These contexts were, of course not walled off from one another. They overlapped and interacted in ways that required people to be able to use more than one language. At the very least, servants and nobility needed to be able to talk with one another.

Coming to live in Yerevan has given me a new understanding of what it’s like to live in a trilingual community, and what life might have been like for those scribes and poets I’ve been thinking about for years. Like London after 1066, Yerevan is a city with a local language and two imperial languages. Armenian (like Middle English) is the language of the local people, the ones whose families have been here for generations. Russian (like Latin) is the language of the old empire, the one that helped shape the present. English (like Anglo-Norman) is the language of the new empire. Unlike the Normans in 1066, the anglophone empire is a cultural one, dominating not with military force but with music, film, international scholarship, and international business. Some of the people of the Harley scribes' England, like the waiters and shop keepers I encounter every day, had to have been able to transition quickly among three languages at need, which is a whole different skill than being able to speak them at all.

I enter this space as a person who had the privilege to grow up speaking the language of the new empire and the good fortune to have learned the language of the old empire to a high degree of proficiency. So how do I choose? In general, if a person seems to be my age or older, I start with Russian because they did school in the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic and would have learned it there. If a person seems younger, I try English. But mostly I don’t choose, when I walk into a shop, a restaurant, a market, the staff decides which language to use, and usually it’s Russian.

I’m a visible minority here. As soon as people see me, they know I’m not Armenian, and most of the time they guess Russian. Only after an extended conversation will it come out that I’m from the US, and only if they’ve gotten me to use Russian words I can’t pronounce or complex grammar I’ve never mastered. Then maybe they ask, or maybe they just give me the hairy eyeball and wonder.

It’s odd to me because Muscovites never mistake me for one of them. They also don’t guess American, though. Taylor says my wardrobe vibe is “comfortable, but high quality” like a middle-aged Scandinavian woman. She's not wrong, and Amsterdam is the only place I've ever been mistaken for a local. But it does make me a bit of an oddity everywhere else.

After being here for six months, I'm ashamed at how little Armenian I've learned. I can say, hello, good morning, thank you, yes, and no. I can also use the numbers 1 and 4, but I confuse 2 and 3, which, in my defense, are very similar. And I only managed to learn these numbers because of the World Cup coverage I watched. International football games don't generally have more than 4 goals on a side.

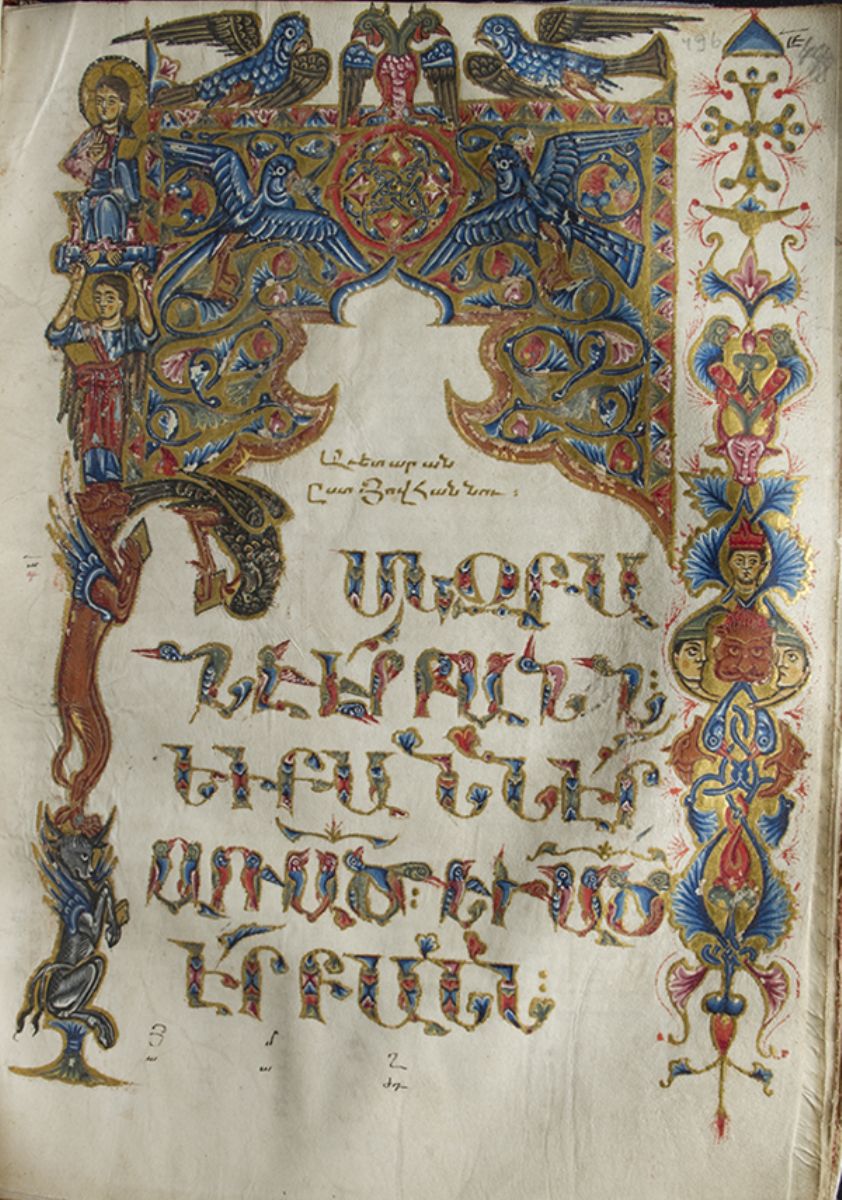

In other places where I've traveled without knowing the language, I have known the alphabet, so I could sound things out in Italy, Austria, Slovenia, or the Netherlands and make educated guesses based on Latin, Germanic, and Slavic roots. The Armenian alphabet, however, remains a nearly inscrutable rebus to me. And not grokking the alphabet means not being able to use menus, signs, and grocery labels as learning tools.

|

| A beautifully inscrutable rebus. Source: Matendaran Manuscript Museum, Yerevan |

My status as a visible outsider becomes a kind of crutch. As soon as they look at me, they expect me not to speak Armenian, so they don't make me try. They just pick an empire, and privilege props me up. And I let it.

Comments

Post a Comment