beginner blues

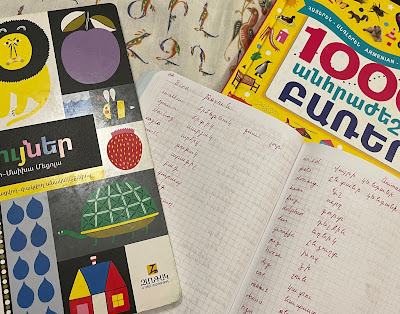

As a language teacher, I find brand-new adult beginners to be the most challenging group to work with. It's hard to fill a class session with engaging activity when the students' tool boxes hold so little vocabulary and even less grammar. As an adult language learner, I am finding being a beginner to be similarly challenging. And I think Nazeli, my tutor, is a saint who is worth every dram I pay her.

For the first nine months I lived here, I was functionally illiterate. I could not wrap my head around the alphabet, so I couldn't even recognize how many of the signs on shops and the labels in grocery stores were Russian or English words transliterated into Armenian letters, words that I could have understood if someone said them out loud.

When the spring semester ended in May, I got serious about making progress and hired Nazeli. After meeting for two hours twice a week since then, I now mostly understand the alphabet. Having as much alphabet as I have now has already opened the city up for me quite a lot. Signs and labels have become learning tools instead of inscrutable rebuses. Still, there are several letter pairs for which I understand the difference but cannot hear it most of the time. This is totally normal because these sounds are not considered distinct letters in English, but it's frustrating nonetheless.

I will write down a word, and Nazeli will say, "No, not k, k!" This will happen again and again throughout the lesson. She usually keeps her cool, but sometimes I can hear the consternation behind the patience. She's actually saying two different sounds, which correspond to two different Armenian letters--կ (voiceless velar stop, unaspirated) and ք (voiceless velar stop, aspirated)--but I hear them both as k (voiceless velar stop). In US English both the aspirated and unaspirated versions exist, but aspirated stops come only at the beginning of a word or the beginning of a stressed syllable and unaspirated stops go everywhere else, so US anglophone brains generally don't differentiate the aspiration. (You can feel the difference if you focus on it. Try saying kick and pop while holding your palm an inch away from your mouth. The k and p and the beginning of each word come with a little puff of air (that's the aspiration) that the k and p at the end of the word don't have.) So I can say both կ (voiceless velar stop, unaspirated) and ք (voiceless velar stop, aspirated), I just find it really really difficult to say each of them in what feels to my anglophone mouth like the "wrong" part of the word, and actually difficult to say the unaspirated stops on purpose at all, as when reciting the alphabet or spelling a word out loud. In US English the aspiration or lack of it isn't a difference that carries meaning, it's just a thing we do in certain parts of a word. In Armenian the difference carries meaning.

I also now have an extensive vocabulary of animals, birds, food, body parts, and cityscape. At this point, I don't actually need to know the names of all the zoo animals or the contents of a primary school classroom. What I really want is an illustrated alphabet book with vocabulary for grown-ups.

An English language alphabet book for grown-ups would have words like:

Aa -- apple, apartment, alliance

Bb -- bookkeeper, budget, bank draft

Cc -- car, car keys, canvas bag

Oo -- office, open floor plan, opposition party

You get the picture, right? Alphabet books created for native-speaker children learning to read a language they already speak are better than no books at all, but they really aren't what adult learners need.

Part of my homework every session is to write sentences, Don't get me wrong--this is a perfectly logical assignment to give. But writing sentences within my pool of vocabulary and grammar is a bit like trying to say something with only a set of magnetic poetry tiles. My ideas keep outrunning the inventory of magnetic bits.

I can successfully construct sentences like

A1: Շունը ունի ծորս ոտքեր, բայց ես ունեմ երկու ոտքեր և երկու արմունկներ:

A2: The dog has four legs, but I have two legs and two arms.

B1: Մենք նսարում ենք նսարանի վրա զբոսայգի մեջ Կոմիտասի արճանի մոտ:

B2: We sit on a bench in a park near the statue of Komitas.

But if I try to say something like

C1: This morning I was looking out the window watching the birds, and they made me happy.

it comes out like

*C2: Այս արավոտ ես նայում եմ պատրաստումը: Կան թռչուններ: Ես ուրախ եմ:

*C3: This morning I look the window. There are birds. I happy am.

I don't have the Armenian syntax for complex sentences or relationships of time. Only lots of experience writing haiku of questionable quality where weird syntax, juxtaposition of images, and line breaks do a lot of the work.

Through the window

Morning birds wheel and turn

Happiness is this

As a person whose job for the last 18 years has been to guide other people through the awkwardness and challenge of language learning as adults, I know that all of this is normal. As a person learning a new language as an adult, I'm bored with simple sentences in the present time frame.

In many ways, I can see that I have made a lot of progress. I can be more polite to people in public. I've met some doggos because I've learned to use կարելի՞ է (may I?) to ask permission. And when I have to ask a clerk or delivery person to speak Russian or English, I can ask them in Armenian, which buys a lot of goodwill, and makes the rest of the conversation easier.

Learning a new complex skill is hard and slow, and I'm grumpy about it.

Comments

Post a Comment